The chemistry of deception: Using science to keep nicotine-based products in check

This story originally appeared in Yale Engineering magazine.

As e-cigarettes and other nicotine products have gained popularity in recent years, several state and federal regulations have been enacted to limit which ingredients these products can contain. The tobacco industry, however, works to get around these laws.

That’s where an interdisciplinary team of researchers at Yale and Duke Universities comes in. It’s made up of engineers, chemists, psychologists, and medical experts who have been diligently studying the appeal and potential impacts of a variety of tobacco products and trying to keep pace with whatever innovations the industry puts forth. The researchers first came together within Yale’s Tobacco Center of Regulatory Science (TCORS), which formed in 2013 to research the influence of flavors and sweeteners in tobacco products, as well as marketing and other related topics.

Read more • Approximately 7 minutes

The TCORS collaboration began when folks in the Yale Department of Psychiatry were conducting research on youth addiction to tobacco products.

“The researchers at the Yale School of Medicine started to see all of these vaping products emerging in the early 2010s, and that youth were preferring things that were fruity or sweet,” said Julie Zimmerman, vice provost for planetary solutions and professor of chemical & environmental engineering. “So they reached out to us asking for our help figuring out what chemicals were in these products so that we could start to understand how user behavior was being driven by the product composition. For instance, how do sweeteners or coolants relate to initiating use or becoming addicted? And how do we prevent teenagers and people who have not used these products in the past from starting?”

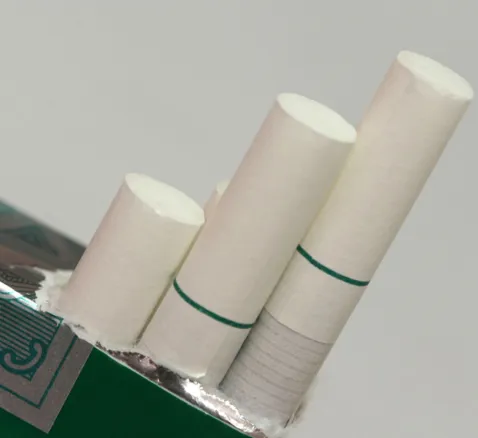

As part of TCORS, Zimmerman’s lab researches the nature and character of chemicals in tobacco products. This includes how flavoring is used in cigarettes, cigarillos and vapes, such as chemical compounds that create a “cooling sensation,” like menthol. The use of menthol is concerning because its cooling effect makes it less harsh for people to inhale. Hanno Erythropel, a research scientist in Zimmerman’s lab, compares it to placing an ice cube in a glass of whiskey to reduce the flavor’s intensity.

“It’s not so much that menthol itself is dangerous, but it is the cooling sensation it provides to make the cigarettes more palatable,” Erythropel said.

In 2020 and 2022, Massachusetts and California respectively banned the use of menthol in tobacco products. These regulations were based on evidence collected over many years, and partly based on the Yale TCORS’ research. Before doing so, the states’ health officials consulted the researchers about their findings.

“Through TCORS, Yale brings scientific results to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the government so that they can consider it and write tobacco product policy that is protective of human health,” Erythropel said.

But the tobacco industry is practiced at finding loopholes in regulations. Several cigarette brands responded to the bans by replacing menthol with a chemical known as WS-3 (named after Wilkinson Sword, the company that first created it to replace menthol in shaving cream) in the California and Massachusetts markets, as the team reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association. With a slight change to the chemical structure of menthol, WS-3 lacks the characteristic odor of menthol — which is what was technically being regulated in the ban — yet it has a cooling effect very similar to menthol, curbing harshness while smoking. The switch was particularly blatant with Newport cigarettes: Other than the word “non-menthol,” the packaging was identical to the previously mentholated product.

“It’s not so much that menthol itself is dangerous, but it is the cooling sensation it provides to make the cigarettes more palatable.

Hanno Erythropel

Research Scientist

“It’s not so much that menthol itself is dangerous, but it is the cooling sensation it provides to make the cigarettes more palatable,” Erythropel said.

In 2020 and 2022, Massachusetts and California respectively banned the use of menthol in tobacco products. These regulations were based on evidence collected over many years, and partly based on the Yale TCORS’ research. Before doing so, the states’ health officials consulted the researchers about their findings.

“Through TCORS, Yale brings scientific results to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the government so that they can consider it and write tobacco product policy that is protective of human health,” Erythropel said.

But the tobacco industry is practiced at finding loopholes in regulations. Several cigarette brands responded to the bans by replacing menthol with a chemical known as WS-3 (named after Wilkinson Sword, the company that first created it to replace menthol in shaving cream) in the California and Massachusetts markets, as the team reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association. With a slight change to the chemical structure of menthol, WS-3 lacks the characteristic odor of menthol — which is what was technically being regulated in the ban — yet it has a cooling effect very similar to menthol, curbing harshness while smoking. The switch was particularly blatant with Newport cigarettes: Other than the word “non-menthol,” the packaging was identical to the previously mentholated product.

It is “the oldest trick in the book,” the researchers recently argued in Scientific American: By tweaking a chemical and making a very slight structural change, the tobacco companies come up with a nominally different chemical — one that isn’t currently regulated — but has essentially the same effect. It’s what the researchers call “regrettable substitution.” That is, a chemical is banned out of concern for human health and the environment only to have it replaced with another chemical that presents similar, if not worse, hazards.

This then leaves the FDA and other regulatory agencies to play a game of catch-up in building up scientific evidence to support regulating the new alternative.

“It’s a moving target for us — constantly trying to understand what products exist, both in the U.S. and globally, and what might enter the U.S.,” said Suchitra Krishnan-Sarin, the Albert E. Kent Professor of Psychiatry, and co-lead of the Yale TCORS.

So how do they keep up? One way, which the researchers advocate, is to take what they call a property-based approach to regulation rather than “one discrete chemical at a time.” One of the collaborators, Sven Jordt, associate professor in anesthesiology at Duke, has been advising regulators in California.

“To create a safe and sustainable chemical world, regulations should target harmful chemical properties rather than individual molecules.

Julie Zimmerman

Vice Provost of Planetary Solutions and Professor of Chemical & Environmental Engineering, School of the Environment and Epidemiology

“We have been advocating that regulations should be based on the activity and effects of that molecule, and not simply the molecular structure,” Erythropel said. “So everything that has a cooling effect, not just menthol, should be regulated; that’s because it’s the cooling effect that has an impact on use rather than an individual molecular structure.”

Importantly, Zimmerman notes, monitoring and chasing individual molecules is expensive, slow, and allows for significant harm to human health and the environment.

“To create a safe and sustainable chemical world, regulations should target harmful chemical properties rather than individual molecules,” she said. “This shift enables intrinsically safe chemicals and could have prevented additives that make cigarettes more appealing and pleasant, rather than seeing those hopes go up in smoke.”

California officials agreed, and the state amended its definition for flavored tobacco last year to also include the sensation of cooling.

In another example of their scientific sleuthing, the researchers conducted an analysis of a series of vaping products called Spree Bar, which are advertised as “nicotine-free” and list the nicotine analog 6-methylnicotine among its ingredients. In all cases, the amount of this chemical in the products was lower by almost 90% than what the company had listed. Analyses of products from other companies also tested positive for 6-methylnicotine, which hadn’t been listed at all. Both cases are concerning, in part, because the discrepancies further obscure an already blurry picture. Very few studies have been done on the safety of 6-methylnicotine (a teaspoon of pure nicotine can be lethal), and there are also questions about its potency compared to nicotine. These findings were also published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

During the same analysis, the researchers also found — for the first time in a vaping product — an artificial sweetener known as neotame.

“That’s also something we hadn’t seen in electronic cigarettes before,” Jordt said. “Neotame is a very highly potent artificial sweetener, rated as 7,000 — 13,000 times sweeter than table sugar.”

After more than a decade, it doesn’t appear that the team’s workload is going to lighten up anytime soon. For every regulation that gets enacted, the industry will introduce a new twist. The researchers are currently looking at IQOS, a new product from the Phillip Morris company that produces vapor by heating tobacco without burning it.

“They have a huge market in Asia for those products,” Krishnan-Sarin said. “They will potentially re-enter the U.S. market again, so we’ll have to keep monitoring to see how people use them.”

More Details

Published Date

Apr 30, 2025