Cracking the case: The art of eggshells

This story originally appeared in Yale Engineering magazine.

It all started when Kiara Matos attended a lecture that mentioned the environmental costs of broken eggshells: About 80 million metric tons of eggshell waste were generated globally in the last year, a number that is only expected to increase. They emit foul odors and spread pathogens. European Union regulations list eggshells as a hazardous waste.

Then Matos, a ceramist who owns Kiara Matos Studio on Orange Street, began thinking about the environmental costs of her own craft. Specifically, that of ceramic glaze, made from calcium carbonate, a mineral that’s sourced from open-cast mines. Doing so disrupts the ecosystems of large areas, often causing irreversible damage.

It turns out that eggshells are made from about 95 percent calcium carbonate also. What if she could replace one with the other, and help alleviate both environmental problems? Was this even feasible? She contacted Jan Schroers, the Robert Higgin Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science, to see what he thought. Schroers was intrigued. That started a collaboration that pairs Yale University with a small local business. It also combines pottery, one of the world’s oldest crafts, with a laboratory equipped with state-of-the-art technology .

Matos, who makes a point of reducing her waste, not using plastic, and even running her kiln as efficiently as possible, thought this was a chance to make a positive impact on the environment.

“So I was like, oh my God, it would be amazing if I can just grab eggshells and grind them and use them, as opposed to mined calcium carbonate.”

In theory, at least. But in practice, would the calcium carbonate extracted from eggshells work as well as the material mined and processed specifi- cally for ceramics glaze? That is, would it provide the same luster, vibrant color, and durability? Matos couldn’t be sure. That’s where Schroers comes in. They’ve known each other for years, back to when their children attended the same preschool in New Haven.

“I called Jan and I told him, ‘I have this idea, can you help me test for durability and safety and all that stuff?’ And he said that he had a student that was willing to grind the eggshells and look at them under the microscope and do the mixing. So we took it from there.”

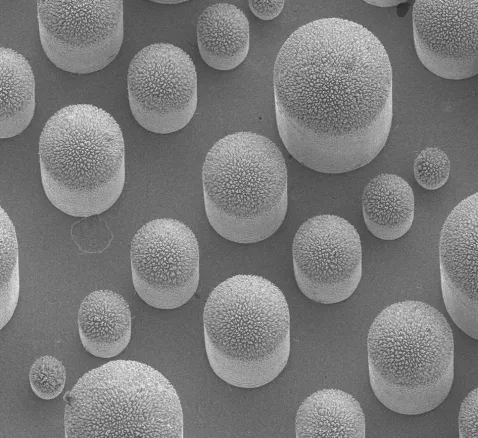

The first task was to figure out a way to efficiently extract the calcium carbonate from the eggshells. Doing so requires burning the eggshells at 800 degrees Fahrenheit, to separate the eggshell membrane. They then used a grinding method known as ball milling to generate fine powder from the eggshell.

From there, they created a gloss glaze with the powdered eggshell, and applied it to flat porcelain tiles. For comparison, they also glazed a set of tiles with the conventionally mined calcium carbonate.. They found no substantial differences, and to the naked eye, the eggshell glaze proved to be just as vibrant and colorful as the conventionally made glaze.

It was a good start, but the real test of a good glaze is how well it protects the ceramics. That’s particularly important for Matos’ work, since much of what she makes is dinnerware that suffers the scrapings of forks and knives. To that end, they used a machine in Schroers’ lab known as a wear tester, which uses a “pin-on-disc setup” to measure the amount of friction and duress that a material can endure.

“It just rotates, like an old record player in a sense, but it always stays in one track and the same diameter,” Schroers said. “Then we went a few hundred times, took it out, and looked at the microscope to see how much material we have removed.”

If no material was removed, they looked closer under a microscope.

“We wanted to compare whether using actual calcium carbonate from the original mine material or the egg- shell was harder or softer,” he said. “We concluded that the wear was pretty much the same with either one.”

Then came the dishwasher test, in which the ceramic pieces underwent about 80 cycles in a dishwasher to test whether the eggshell glaze leached at all. Again, they found success, as the glaze proved strong against the dish- washer treatment.

If anything, Matos said, she prefers the eggshell glaze. “It’s less bubbly, and I love the color of it. There is a lot more we can do with this.”

The tests encouraged Matos to convert her business entirely to using an eggshell-based glaze. Getting enough shells turned out to be pretty easy. Her husband owns G Cafe bakery next door to her studio, so she gets plenty of eggshells from him. The owners of Union League Cafe on Chapel Street, which uses Matos’ ceramic dinner plates, also donate their shells. She hopes eggshell-based glazes will catch on.

“Ceramics are one of the most long-lasting materials we have ever made,” she said. “So it would be great if we could take the eggshell and turn this wasteful, fragile thing into a very durable, useful thing.”

More Details

Published Date

Jun 25, 2025