Faculty Spotlight: Jaehong Kim / Engineering with purpose, innovating by design

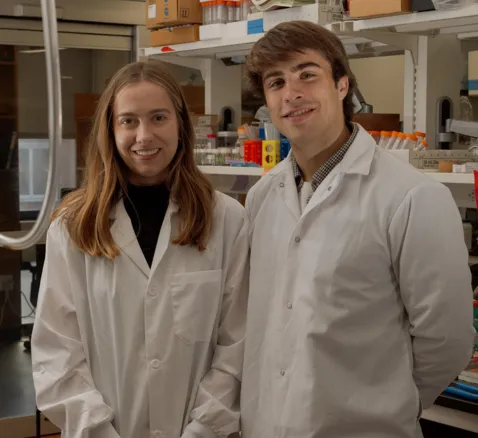

Written by Natalie Haase '27

I first met Dr. Jaehong Kim in the fall of 2024, when I took Environmental Engineering Lab Practice, co-taught by him and Dr. Colby Buehler, one of the most formative courses I’ve taken at Yale. We had outdoor lectures in East Rock Park, tested drinking water quality in the field, and trained in Dr. Kim’s Mason Lab on techniques I now use in my own research – from pipetting to High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). HPLC is a powerful analytical technique used to separate, identify, and quantify chemical components in liquid samples by forcing a sample along with a solvent through a column with solid particles under high pressure. More than any skill, however, what I remember most was how much Dr. Kim cared – about his work, and how it impacted the world, and perhaps even more so, his students, and their trajectories, learning and impact on the world. He met students exactly where we were, combining rigor and curiosity with a rare kind of flexibility. When I learned later that he had designed the scientific art hanging in his lab’s office, it all made sense: this was someone who not only engineers solutions to save lives, but brings a creative, human-centered lens to everything he does.

Jaehong Kim, the Henry P. Becton Sr. Professor of Chemical & Environmental Engineering, develops life-saving water and air quality technologies, teaching students to create practical solutions in developing countries.

From Material Science and Environmental Engineering to Meaningful Impact

Kim’s path to Yale began in Korea, where he studied chemical engineering – with a major focus on “applied chemistry” – through his master’s degree. “Environmental engineering didn’t exist in the university he was in at the time,” he reflects. But he found himself drawn to membrane separation and biotechnology, especially its potential to protect nature and human health. That led him to pursue his Ph.D. at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, focusing on disinfection technologies that could remove waterborne pathogens.

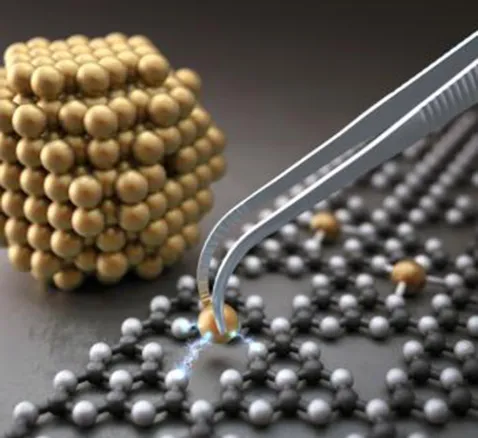

As he read reports of global waterborne disease, particularly in resource-limited settings, a conviction took root: research could – and should – save lives. That mindset stayed with him through his early years as a faculty member at Georgia Tech and brought him to Yale in 2013. Here, he continues to develop novel water treatment technologies powered by sunlight, nanomaterials, and catalysis – systems designed for impact at both the household and industrial scale.

“Engineering should be about making something great for humanity and saving people’s lives,” he says. “That has always resonated with me.”

Teaching by Doing, Teaching by Improvising

Fieldwork is central to Kim’s pedagogy. He’s designed and led courses where students travel to developing countries to design, test, and implement technologies – from air quality sensors wearable by mothers in kitchens to solar-powered disinfection units. In Nicaragua during a class field trip in 2016, for example, a border customs confiscation of equipment turned into an unforgettable learning moment: with no gear and therefore all the previously established plan voided, the students had to rebuild everything from scratch. “They said it was the best educational experience they ever had,” Kim laughs. “And I barely taught anything. I just improvised.” But to him, that’s what real teaching is about—cultivating intrinsic motivation, not chasing grades.

In another field anecdote, students insisted on testing water samples before even stopping to eat after a 12-hour day collecting data in the desert. “They were exhausted. I said, ‘This isn’t a Ph.D. dissertation!’” he recalls. “But they just wanted to get it right. That kind of commitment…it’s not something you can force. It’s something you unlock.”

Research that Translates

“Engineering should be about making something great for humanity and saving people’s lives. That has always resonated with me.

Jaehong Kim

Henry P. Becton Sr. Professor of Chemical & Environmental Engineering

One of Kim’s favorite projects? A solar disinfection window that changes color to indicate when water is safe to drink. The technology drastically reduces wait times (from 24 hours to under 30 minutes) by adding a food-safe dye that absorbs sunlight to disinfect water. When the color fades, the water is ready to drink. It’s a simple, elegant solution – developed in partnership with the Yale School of Architecture – that could have major implications in regions without reliable clean water access.

From electrochemical cells that generate hydrogen peroxide on demand to catalytic membrane systems tailored for household or industrial wastewater, Kim’s lab is constantly working to bridge the gap between bench-scale prototypes and field-ready systems. “The hardest part isn’t just making something that works in the lab,” he notes, “it’s making it work in the real world, under real constraints.”

Global Vision, Local Action

Kim is a founding director of KCITY (Korea-Center for Industrial Technology-Yale), a Yale Engineering-wide initiative built in partnership with the Korean government and industry. Located in 17 Hillhouse Avenue, KCITY supports interdisciplinary research with Korean industries on AI, robotics, materials science, and environmental technology. With six principal investigators across four core projects, the initiative reflects Kim’s commitment to global collaboration – and to the idea that engineering at Yale should be both outward-facing and deeply applied.

He’s quick to remind his students: humanitarian work isn’t just about showing up in a community for a short-term project. “If everyone’s working on distributing vaccines, for example, who’s developing the next one?” he says. “Being in the lab, testing materials, running HPLC – it doesn’t always feel like impact. But that’s where lasting change begins. If you’re at a place like Yale, you have the education and opportunity to invent solutions that can scale.”

Engineering With Purpose – and Personality

Beyond the lab and the classroom, Kim’s personality shines through in subtler ways: the hand-drawn graphics on his journal covers, the sculptures in his office, the perfectly formatted presentation slides, his unexpected skill on the electric guitar, inspired, in part, from a lifelong love of Metallica (a hallmark of his artistic upbringing – his mother ran a private art school, and both his sisters majored in art). “Visual art has always been part of me,” he says. “I like things to be beautiful. Even science.”

More Details

Published Date

Nov 13, 2025